accesses since June 31, 2007

accesses since June 31, 2007

copyright notice

copyright notice

accesses since June 31, 2007

accesses since June 31, 2007

Hal Berghel

A few years back I had a very large integrated marketing company as a client. During lunch with the COO I let it slip that I was averse to junk mail. He looked up over his salad and said, “in our industry we prefer the term ‘unsolicited mail’.” Some say “potato,” some say “tomato.”

I mention this because my slip was telling of my world view. In the present context I do not recognize “unsolicited email” as a legitimate entity. If it isn’t email I asked for, directly or indirectly, it’s junk, pure and simple. For the past week, I’ve been keeping a tally of junk mail received for this column. At the client, I’ve received slightly over 2500 emails, of which 1652 were identified as junk by my client-side filter. Of the remaining 865 emails that got through to my inbox, over 300 were junk (false negatives). At the server, the volume is greater, but the server filters out the most egregious violations without my knowledge so I don’t see them.

We’ve spent gazillions of public monies, invested a lot of university professor’s time, encouraged dozens of start-ups, developed a variety of new technologies, and passed tough legislation, and yet the problem doesn’t go away. Why is that? I have a partial answer: getting rid of spam is akin to shoveling sand into the tide – it’s an uphill fight against nature. The best we can hope for is a momentary relief.

THE LEGISLATIVE PREROGATIVE

Congressional legislation is almost always reactive: the sequence is calamity, public outcry, public hearings, lobby influence, legislation. So since spam has been a problem since the early 1980s, it was entirely reasonable that Congress should consider doing something about it in 2003 (see sidebar).

The only thing that has come out of this consideration is the anemic Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003, or CAN-SPAM Act for short (Public Law 108-187, S. 877) enacted November 25, 2003 and effected January 1, 2004. I'll outline some of its provisions.

The CAN-SPAM Act

Focus on (1)-(6) for the moment.

SPAM SPREAD

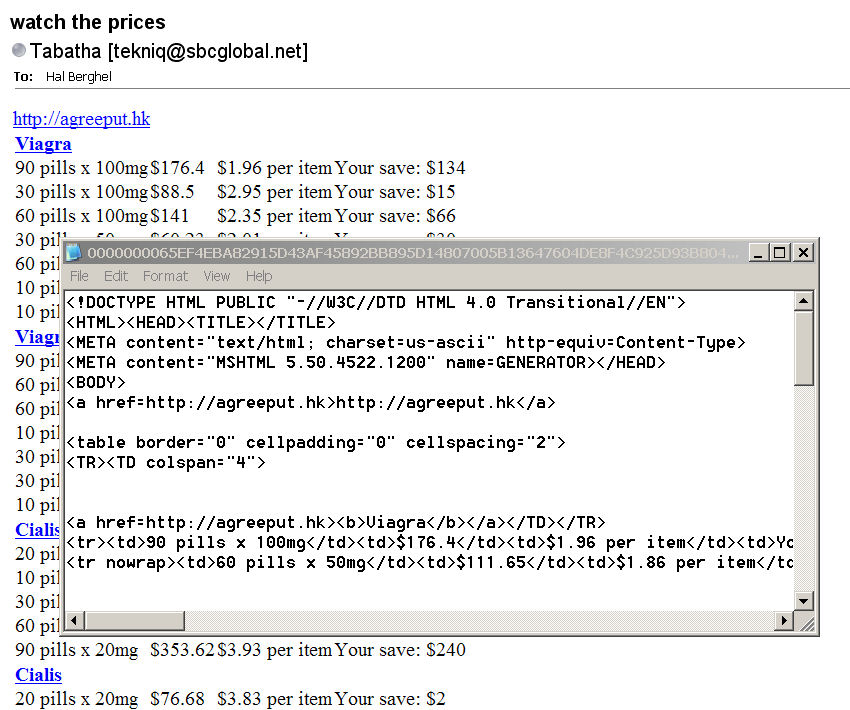

I begin with a modest example. Figure 1 is an example of generic spam. Nothing imaginative, just pedestrian spam to sell potency pills.

Figure 1: Generic HTML Spam

We note that the spam is formatted in HTML for convenience, probably by a Microsoft product. No Dreamweaver needed in this app.

Of course, the email address can't be verified, but that's no surprise. So, we look a little deeper into the header and find that the source was actually 59.115.1.5. A WHOIS reveals that that's a large (10 class B addresses) ISP in Taipai, so the spam source was likely one of their customers. Now, the operative question is “Was the customer actually the spammer or merely a zombie?” What do you think the chances are that we can get Chunghwa Telecom Co., Ltd. to spend a half-day to find out for us? So we next chase down the <agreeput.hk> domain. Agreeput.hk resolves to 221.127.94.208 which is a four class-B web hosting service in Hong Kong that in all likelihood has no problem with spammers using this service to sell legal drugs. Compare our observations with the provisions of the CAN-SPAM Act, above. Even our toothless, vanilla example definitely violates at least provisions (1)-(5), and possibly (6) as well. The U.S. Government has no control over foreign users, and is unlikely to use political and economic pressure on anyone who might be a potential ally. CAN-SPAM is totally ineffective in this case.

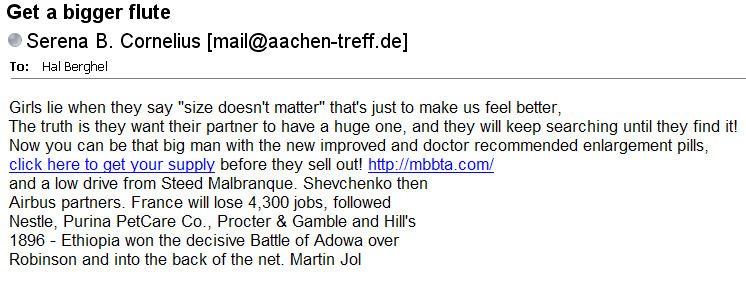

Figure 2 is the “enhanced, generic” spam. It's Figure 1 with a tad bit of stealth. Needless to say, there is no Serena B. Cornelius. But the header shows the source as 70.123.169.171 which belongs to a fairly large ISP in Virginia . So large, in fact, that Serena's doppelganger is unlikely to show up on their radar. The minimal stealth comes from the last four lines. The irrelevant text is there to fool the spam filters that use Bayesian analysis on the content of the email. This example score's low because the content wasn't recognized by my Bayesian analyzer.

Figure 2: Vanilla Spam with Chocolate Chips

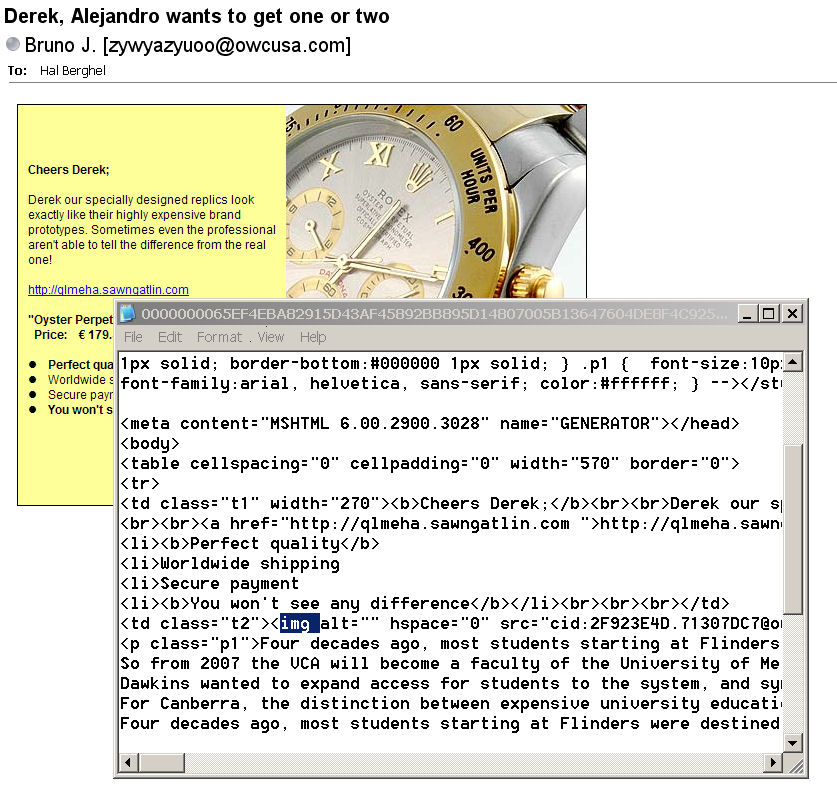

Ratcheting up again, we come to Figure 3. In this case, we have vanilla spam with chocolate chips and a cashew. The cashew is the image (highlighted). This spam avoids spam filters that do not OCR embedded images – a very time-consuming, server-side process as some of you can attest. In fact the only significant text is the irrelevant text below the image link, so there's not much for a Bayesian analyzer to do. It's kind of like parsing a string of digits – time lost but nothing to show for it.

Figure 3: Graphical Spam

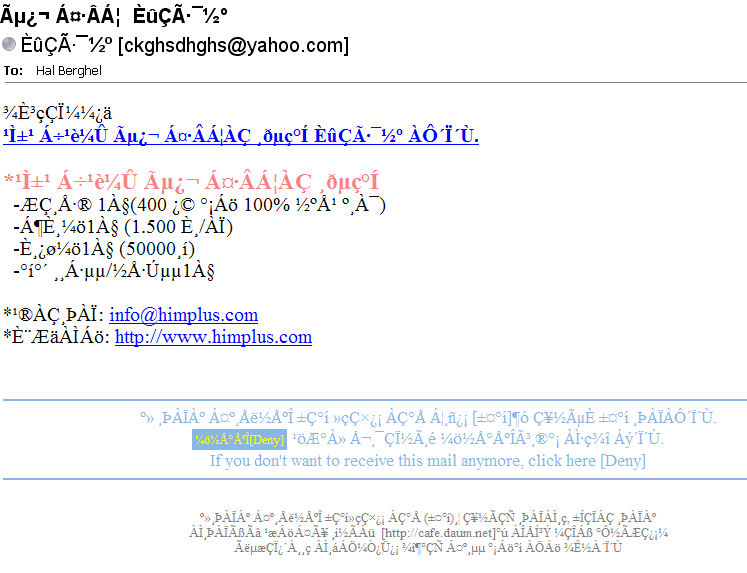

We'll conclude with a recent trend – spamming the world with unusual character sets (Figure 4). This is our vanilla, with chocolate chips and fish bait. Look at the opt-out link at the bottom. Is this reasonable and prudent? Nope, because the email addresses from responses are likely harvested and re-sold or traded. Spammer “opt-out” links are never to be trusted. Why? Because responses are proven “hot links”- the only way that the user could elect to “opt-out” is if the spam got through. In other words, by “opting-out” the user is actually “opting-in.”

Figure 4: Spaghetti Spam

CONCLUSION

Flash back to my spam tally in the second paragraph. The email examples above got through my server-side filter AND my client-side filter. How did this happen?

Well, that's the cost of avoiding false positives. A false positive is a legitimate email (possibly from an employer, client, family member, mortgage holder, DMV, etc.) that was mistakenly identified as spam. In my line of work, I can't afford false positives for economic reasons! If I tighten the weave of my email filters sufficiently to block examples like those above, I will inevitably snag a critical email from someone I need to communicate with. False positives will always be a problem as long as more people know us than we know. In email client terms, false positives will remain a problem as long as it's possible there is at least one important person who is not in our current contact or safe-senders' lists. And no CAN-SPAM Act can ever legislate around this fact.

So if I can't maximize my filtration, my first line of defense is the good will of bad spammers. That's right, I have to rely on the spammer to conform to anti-spam legislation. What do you think the chance of that is? Exactly. That's the uphill fight against nature rearing its ugly head. Spammers won't listen to Congress, and certainly won't listen to us. So spam is here to stay. And every post hoc remedy will just produce a new wave of more sophisticated spam.

There is hope with Internet II because packet-authentication is built into the protocol. However, think of this in terms of your own target retirement date. The internet started in the late 1960s, but didn't become popular for most people until the 1990s. The internet2 consortium started 10 years ago, and currently operates at 9gbps over 30,000 km, but how many of you have the protocol embedded in your enterprise? Most of us will be retired by the time that internet2 packet authentication affects spam, and by that time Spam2, the Sequel will have arrived.

By the way, visit Hormel's www.spam.com website for a smile.

UNENACTED LEGISLATION:

No spam on our legislative calendar, said the Congress. 2003 was a boon year for discussing spam, but not a good one for doing much about it. The following bills all shared the same fate: death in committee.

Hal Berghel is (among other things) Director of the Center for CyberSecurity Research (ccr.i2.nscee.edu) and Co-Director of the Identity Theft and Financial Fraud Research and Operations Center ( www.itffroc.org ). He also owns the consultancy, Berghel.Net.