Background:

Interviewee: Hal Berghel, Computer Science Professor, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Honors: ACM Fellow, Distinguished Lecturer, ACM Distinguished Service Award, Outstanding Contribution Award, Outstanding Lecturer of the Year Award (four times) and was recognized for Lifetime Achievement in 2004; ACM Computing Reviews Notable Article 2013, 2014 and 2016, Re IEEE, Fellow, IEEE Distinguished Visitor, IEEE Computer Society Distinguished Service Award, IEEE Computer Society Meritorious Service Award, IEEE CS Golden Core Award, Sundry Who's Who editions (e.g., World, America, South/Southwest, Science and Engineering, American Education, Information Technology, American Men and Women of Science, American Teachers, etc.)

CH: Hal, you are one of the most prodigious writers and contributors to the computing science discipline, via a wide variety of contributions. We'd like to focus this interview on a few parts of those widespread activities, after a brief ‘personal' introduction.

CH: Where were you born and raised, and what piqued your interest in computing?

HB: Born and raised in the Midwest during the Ike years. I hold what I consider basic midwestern values to this day. In graduate school, my interests were logic and linguistics, and that led me to two hot areas in the 1970's: computational logic and computational linguistics. After my PhD, I taught Management Information Systems for a few years and developed, taught, and oversaw a business college computing literacy program. That program was so successful that it was absorbed by the department of computer science as the resident cash cow for the department, with me along with it. It was a huge credit hour producer (north of 5,000 SCHRs per semester as I recall), so computer science used the program to justify additional resources, and they recognized that hiring me full time was a small price to pay. I accepted the CS position on the condition that I would eventually be considered for a regular faculty appointment. That relationship worked well until both the chair and best known senior faculty quit. As it turned out, that was a blessing in disguise when I discovered in the 1980s how lucrative faculty appointments in computer science could be. My life hasn't been the same since.

I morphed my research interest in computational logic and linguistics into experimental computer science and spent quite a few years conducting research in expert systems, approximate string matching, software metrics, image recognition, and eventually internetworking – including web development, interactive programming, and multimedia. By the 1990's my interests had migrated to internetworking and computing security. I was introduced to computing security initially through the published work of Dorothy Denning and Gene Spafford, and that led me to SANS classes in the late 1990's – since I was most interested in the practical side of computing and network security.

CH: Describe your schooling, both formal and informal, that led to your wide perspective re computer science and IT.

HB: My formal post-secondary education, as I mentioned above, was driven by my interests in philosophy, logic and linguistics. My undergraduate degree was in philosophy, and the areas that interested me most were formal logic and the philosophy of language. That led me to pursue graduate degrees in these areas. I was enrolled in five academic programs, but only received degrees in four: a bachelors, two masters and a PhD from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. By the time I received my PhD, I was already taking graduate classes in computer science - formal languages and automata theory, programming languages, and computer architecture seemed to be the best fit with my interests at the time. My move to computer science was coincidental to the beginning of the microcomputer revolution, so I built my research program around microcomputer networks such as they were in the day. I also created a consulting company to help professionals automate their offices with networked microcomputers at the time which proved to be particularly lucrative. I held a great fascination for things computing and couldn't believe that I could do what I wanted and actually get paid for it. What a great life, I thought, and never looked back. After my PhD, the computing and internet revolutions just kind of carried me along with them, providing me with an endless supply of alluring computing and networking temptations along the way.

CH: After graduating, outline your career progression for us. If I have this correct, you spent a number of years in a variety of both academic and industry experiences prior to joining the faculty at UNLV. (My hunch is that this broad exposure was formative in terms of giving you a wider perspective than many academics exhibit). We'll come back to the UNLV work post-2000 later in the interview.

HB: As I mentioned, the academic program that I oversaw was moved from the business college to computer science where it remained for many decades after my involvement ended. At that point, my career forked into consulting and academics. I set up my first research group (e.g., acquired external funding for resources and staff) and I began taking on the role of a research administrator. So within the first few years of my PhD I was administering an academic program, running a research group (in expert systems and computational linguistics initially), teaching, and consulting – not activities that will lead to a Turing Award, but it was sure rewarding and a lot of fun. After a few years, the computer science department focus changed when the faculty that I was closest to professinally left, so I took a position at the University of Arkansas – which was also great fun. That would have been in the mid-1980s. At this point, I limited my consulting to a very few clients who were the most fun and remunerative, and ramped up my academic research and external funding (the two are considered to be indistinguishable only in colleges of engineering, b.t.w.)

The Arkansas experience was a trip. The CS and CE programs were in their infancy then, so the faculty quickly doubled with exciting new PhDs from some pretty good graduate programs. This was great for me because the new faculty were (roughly) my age and shared my interests in computing. The only problem was that the computing and networking infrastructure in Arkansas was pretty primitive in those days. I got by because I brought my own lab with me so I didn't need much start-up money. Perhaps the greatest obstacle to everyone, however, was the lack of direct Internet access. At that time the campus was linked through IBM's Bitnet, so access to the internet was indirect, convoluted and bothersome. One of my first projects was to encourage state policymakers to get that changed, so together with John Talburt (associated with a sister campus in Little Rock) we set up a state computing society and drew in the executives of the companies with the largest IT footprint: Acxiom, Wal-Mart, JB Hunt Trucking, Arkansas Systems, Systematics, etc. (for anyone interested in such arcane topics, John Talburt's account has been memorialized in a living history @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gORpvvpDNIs (~35:00). Our motivation was to draw the executives into the discussion as they had access to, and influence with, the politicians (Clinton was the governor at the time). Within a few years, the Internet access issue was resolved in the university's favor, and we went on to galvanize indigenous researchers across multiple campuses into a research center under my direction that provided the initial boost of external funding into computer science in the state in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was at this point that I got interested in ACM volunteer work.

In the late 1990's the Arkansas computer programs imploded (we lost something like 1/3 to ½ of the younger faculty) so I moved to UNLV and basically did the same thing as I had before, but this time with the additional twist of chairing the department of computer science. Throughout my entire academic career I have always been some variation of administrator-teacher-scholar, having run several self-funded academic research centers as well as chaired/directed several academic programs. I have been the chair/director of two academic departments four times and served as an associate dean of engineering for six years while teaching and conducting research in my areas of interest.

CH: Early on, you got very involved with ACM, an interest that seemingly never abated. How did this happen?

HB: While at Arkansas I partnered with Don Fisher at Oklahoma State to expand a conference he started (the Oklahoma Workshop on Applied Computing) into a national effort in order to gain increase the visibility of academic computing in the region (initially, AR, OK, MO, KS, NE, IA) The regional universities were not known as beacons of computing enlightenment in the 1980's, so it occurred to me that we'd all be better off if we had some galvanizing resource to bring us all together (cross-fertilization of research and such). Don made the first effort in that direction, and I followed through with it.

I received some NSF support to take the OSU workshop international, and that's where the ACM Symposium on Applied Computing began in 1990 (it still exists to this day - http://www.sigapp.org/sac/ ). That proved so successful, that I proposed and initially chaired the ACM Special Interest Group in Applied Computing, which was approved and also still exists today. Those two activities got me connected with the ACM leadership, and that connection morphed into a decade-long appointment to the ACM Publications Board and a long association with the ACM Local Activities and Membership Boards. The Pubs Board added the ACM digital library to its portfolio during that time – a project that was initiated by Pubs chair Bill Greuner and carried through to perfection by his successor Peter Denning and ACM Executive Director Joe DeBlasi. ACM.ORG was also developed while I was on the Local Activities Board. Bill Poucher and Joe DeBlasi led that effort, and as I recall Poucher worked out a deal so that ACM.ORG could be hosted in Waco and administered by his former Baylor students. I watched both of these efforts unfold brilliantly. Time recorded that both were inspired ideas well ahead of their time and of other disciplines. I'll tell you a funny story about the DL. Peter Denning asked Mark Mandelbaum to contact PayPal to investigate how PayPal could be used to market ACM products and services. I recommended a slower, measured approach as I just couldn't see the value proposition in PayPal at that time. I couldn't understand why anyone would use PayPal instead of their credit cards for online transactions –ACM or other. In retrospect, rampant identity theft and bank card fraud would make PayPal indispensable for me, but I didn't see that back then. But Peter did, fortunately.

CH: You were a frequent contributor to CACM for many years. How did that come about?

My association with CACM began in the early 1980's. Somehow I managed to enter into a discussion with CACM managing editor Gene Dallaire about the so-called “Apple Bill” which was vigorously supported by many politicians and industry executives at the time. I told him that I thought that this was a taxpayer rip-off of the first order, and that it would live on in our memories as just another example of failed wealth transfer from the taxpayer to large corporations. Apparently he thought my position might be interesting to the CACM readership, so he encouraged me to write up my thoughts, and the resulting article, Tax Incentives for Computer Donors is a Bad Idea, became the March, 1984 cover feature in CACM. What Gene didn't tell me was that he decided to spice up my article with a printed response from the key sponsor of the legislation, California representative Pete Stark. Needless to say, Stark was not keen to have any academic computer scientist drop guano into his legislative punch bowl, and so he attacked me in print in CACM for single-handled halting the educational advancement of underprivileged children - completely evading my point that the main effect of the Apple Bill would be to encourage product dumping of obsolete compoters and that it would not advance computer-assisted education in any important way. As I pointed out in that issue, Apple stood to generate more revenue from the donations of obsolete, unsalable Apple IIs than it would have ever received by selling them at full retail. (I encourage readers to look up this exchange in the ACM DL if for no other than historical interest. It's still relevant 40 years later as the DNA of crony capitalism hasn't abated.)

I continued to publish in ACM and CACM for decades to follow. One day in the mid-1990's I pitched the idea of a column to Diane Crawford, who I believe succeeded Gene as managing editor. She agreed and The Digital Village column was born. That quarterly column ran in CACM for nearly 15 years and gave me wide latitude to discuss technical policy and social issues associated with computing and networking. When Digital Village ended, Ron Vetter who was EiC for IEEE Computer at the time asked if I would be willing to do something similar for IEEE Computer, and I've been writing my Out-of-Band column ever since. Digital Village and Out-of-Band span over 25 years at this point, and have brought me as much satisfaction and enjoyment as any other professional activity in my career. Thanks Diane and Ron! A few years ago, Ron's successor as EiC, Sumi Helal, asked me to create a second column in Computer called Aftershock. I recruited John King (UMich) and Bob Charette (ITABHI) to help with Aftershock, which remains a quarterly staple.

CH: How did you get connected with the ACM Publications Board?

HB: I''m not sure. I have a hazy memory that Dave Oppenheim recommended me to Pubs Board chair Bill Greuner. This must have been around the late 1980s. In any event, Bill asked me to join, and when he stepped down Peter Denning asked us to stay on and so I remained on the board through Bill's term and Peter's two subsequent terms as chairs. It was during Peter's terms that the ACM Digital Library was successfully implemented. While I was not directly involved with the decision making, I witnessed the evolution of the DL first hand under Peter, Joe DeBlasi and Mark Mandelbaum while I was on the PUBS Board. I would be remiss if I failed to mention that all three were critical to the DLs early success. I still consider it a privilege to have been party to some of the discussions. One final note. Mark asked me to write a FAQs column for the DL. I created and wrote four installments of ACM Digital Library Pearls in 2001, and then stopped after 9/11 as many of us re-evaluated priorities. There wasn't anyone at ACM that wasn't directly affected by that tragedy and it really changed the mood at 1515 Broadway. At that time, I began to pull away from my pro bono volunteer work.

CH: How did you get connected with the ACM Local Activities Board?

HB: The Local Activities Board (which became the Membership Activities Board somewhere along the way) was the ACM board with which I was most engaged from the late 1980s to about 2000. By 2000, Dave Oppenheim and Joe DeBlasi had left ACM, the tone of ACM had changed to become more profit-centered and less member-centered and I decided to pack it in regarding my volunteer activities (except for the CACM column).

After the Web was launched in 1989, I began doing a lot of prototyping of online “interactivities,” initially server based CGI then later host scripted. My teaching experience led me to a familiarity that I thought might be useful to ACM to attract and retain members, and so I did a lot of pro bono Web development for ACM.

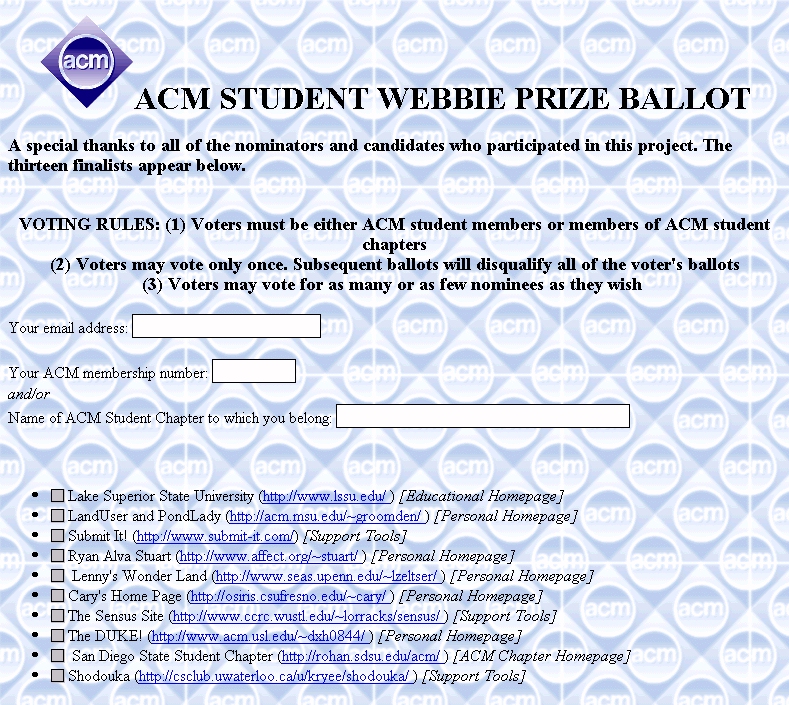

Dave Oppenheim (who succeeded Poucher as LAB chair) and Joe DeBlasi were always open to my ideas – no matter how unusual - and managed to find ways to help me fund them. One early project I did for ACM was the ACM Webbie Prize for noteworthy ACM student chapter and student chapter member websites that I created in the mid-1990's. There is an interesting story behind this. First, I originally called it the ACM Webbie Award, launched it, and started giving away recognitions to chapters, but after the first year Pat Ryan informed me that only the ACM Council could use authorize “awards” and I hadn't bothered to consult them. My bad. So I had to change the recognition to the “Webbie Prize”. Second, our Webbie preceded the Webby Award by quite a few years. By the time the Webby came along, we had already given several of our Webbies to ACM student chapters. In retrospect it would have made sense for me to have had the term trademarked on behalf of ACM but I never thought in those terms. Third, the ACM Webbie prize winners were determined democratically by online vote. All ACM student chapter members were allowed to vote on an online ballot of candidate website URLs. That necessitated the development of a CGI online voting site which my students and I developed and put on ACM.ORG. This ACM online Digital Ballot Box was used for all of the Webbie competitions that I oversaw. [cf. ACM Webbie Ballot - IMAGE ATTACHED] After a few award cycles, I turned over the entire Webbie project to the student volunteers who were involved in the Crossroads effort where it died for reasons unknown to me. While we're on this topic, I worked with the Student Chapters in Mexico that I helped create and bring into ACM to create the first foreign language (Spanish) edition of Crossroads. I always felt that the idea of an award for web creation was something the ACM should take an ownership in, and the Webbie was a uniquely ACM product. I remember suggesting to Joe and Wayne Graves that ACM should retain and date stamp such innovations to prevent future patent infringement claims. I'm certainly no patent attorney, but it was my understanding that if ACM could document that they were using a technology prior to the issuance of a patent, they could continue to use it without fee. But, no one seemed too concerned, and the web award that comes to mind today isn't ACM's Webbie.

Another LAB/MAB project that I was involved with was reviving the ACM Distinguished Lectureship Program. Bill Poucher indicated that if something wasn't done to add prestige and accountability to the program, he felt it would be cancelled. I had been a lecturer for many years by that time and really believed in the program, so Bill offered the directorship to me and gave me a year and a budget to fix it. When I looked into the management of the program I saw that the biggest problem was a lack of accountability. The volunteers in charge made no effort to ensure that value was provided to the chapters or ACM. When I asked to review the feedback from the chapters, I found that chapter feedback wasn't being systematically collected. So I created an oversight board of five individuals with staggered terms, the chair of which would be the individual serving in their fourth year. That would provide the needed institutional memory. Then I posted online requirements – e.g., chapters had to ensure a minimal audience size – 50 as I recall – to ensure cost effectiveness in order to get ACM to cover the expenses. There was documentation in the files that DLP had been sending lectures to give talks to 3 and 4 people! I then added a mandatory feedback mechanism from the inviting chapters: they had to provide feedback on the ACM Lecturer and event along with their request for reimbursement for expenses. I made the summary of the scores available on the Distinguished Lectureship Program website that I created, and then started the lecturer of the year recognition for the speaker with the highest overall score and gave away nice engraved gifts (Spacepens, clocks, etc.) bearing the DLP and ACM logo to all lecturers that participated in the program each year. The inherited problems with the program vanished quickly. Lecturers who were poorly received by the chapters were either dropped or chose not to continue, and the best were retained with new ones added after careful screening. In a year or two, the chapter requests for lecturers doubled, then tripled and by the third year the program was running so smoothly that I could phase myself out as director and turn the program over to the committee I created. That's in part why I received the Lifetime Achievement recognition that you mentioned. It reads, in part, for “successful reorganization of the program when its very survival was at risk… and passionate advocacy on behalf of the program.” I'm reading this from the plaque as I type this as it's still hanging on a wall in my office. I recall Lillian Israel asking me about these details long after I discontinued my volunteer work with ACM. I hope that some of these initiatives are still being retained, but I don't know.

One of my last efforts on behalf of the DLP aside from securing continued funding through TOP and MAB was to create the ACM Video Podium. Since the repaired DLP already hosted chapter talks by distinguished lecturers, I came up with the idea to videotape them so that ACM could build a permanent video archive of these talks for posterity. (Remember, there was no YouTube in 1995! In fact, there wasn't much Internet in those days.) Also, this way even the smallest ACM student chapters could benefit from the DLP even if they couldn't attract a large enough audience to justify an in-person lecture. So, I worked out a partnership with Abe Kandel at the University of South Florida to use their FEEDS network studio to record some lectures. I would occasionally send a lecturer on a tour that would include USF, and we would use 3-camera, real-time editing to make a VHS videotape master that Fran Sinhart at HQ would duplicate in house on demand. This really worked pretty well. Of course now one could produce equal results with an iPhone, but iPhones wouldn't be available for another decade (neither would DVDs and streaming videos for that matter). I remember spending time in the control room with the studio manager doing real time editing – one feed from the overhead projector or computer, one wide camera, and one camera following the lecturer – and we just hopped back and forth between camera feeds. I was amazed on how well that worked, but it worked even better when the studio manager offered us an hour or two of post-production for a nominal cost. We created a video library of a dozen or so titles and gave them away to interested student chapters around the world – all for the cost of a VHS tape and postage. This project continued for many years. I still have some of the tapes in my office somewhere and my hunch is that others are to be found in ACM storage closets! I combined this with the ACM Regional Magnet Event project whereby larger meetings and conferences could get a DLP lecturer as a keynote speaker for free if they opened the lecture to local ACM and chapter members. The idea there was to spread the ACM's word to the greatest number at the least cost per contact. The RME met with limited success because the meeting organizers couldn't be counted on to reliably their activities to ACM members and chapters in their area once we agreed to fund their keynote speaker. We determined that the HQ and volunteer overhead was excessive, and I eventually cancelled the project. The only place that the RME was a true success was Mexico. I partnered with Jesus Flores Morfin to expand ACM's influence into Mexico and Central America using the DLP and RME as magnets. Dave Oppenheim also supported the concept of steeply discounted ACM student memberships (a few dollars) to all foreign computing students which brought in student members by the thousands. David Arnold who followed Dave helped me expand this program beyond Central America until the early 2000s when I left ACM. I thought at the time – and still think – that this was one of the most worthwhile activities ACM supported. But John White (who followed Joe DeBlasi as Executive Director) felt otherwise, and shifted MABs focus to initiatives such as the ACM Digital Driver's License, etc. but by that time Joe, Dave, David and I had all left ACM. But I digress, so let me back up to the mid-1990s again. One last thought. By the time I left ACM, the average DLP cost to ACM per audience participant was in the $1-3 range. The ACM got a lot of promotion and good will for very little expense.

After the Lectureship Program was restored, I moved on to create the ACM Technology Outreach Program (TOP). [I note that the TOP splash page is still on the ACM Web archive @ https://www1.acm.org/top/ ] As I mentioned LAB evolved into MAB (Membership Activities Board). Several things took place concurrent with this change. Bill Poucher had already moved over to direct the programming competition, Dave Oppenheim took over as chair of MAB, and I became vice-chair. Dave and I organized MAB so that the Technology Outreach efforts I was about to begin (including DLP) could have a semi-autonomous budget which enabled me to do longer-term planning, and this made TOP viable as I didn't have to go to Dave for line item approval. I envisioned TOP as a collection of experimental prototypes to engage based on an online platform presence on ACM.ORG. ACM staff was already moving along the lines of marketing products and services online, so I envisioned TOP as a proof-of-concept sandbox. One experiment was my Email: Good, Bad and Ugly interactive website that was on ACM.ORG for a year. The website allowed visitors to contribute feedback to the strengths and weaknesses of email which was available for the visitors to review. These days the website would be called a blog, but no one used that term in those days. I reproduced some of the responses in my April, 1997 CACM column of the same title. I thought my idea of an “interactive aggregator of online content” held great promise. Unbeknownst to me, Ward Cunningham had developed a much more sophisticated site around the same time and called it a wiki, and the name stuck. For this we are indebted to Ward, for a name like “Interactive aggregatopedia” would never have stood the test of time.

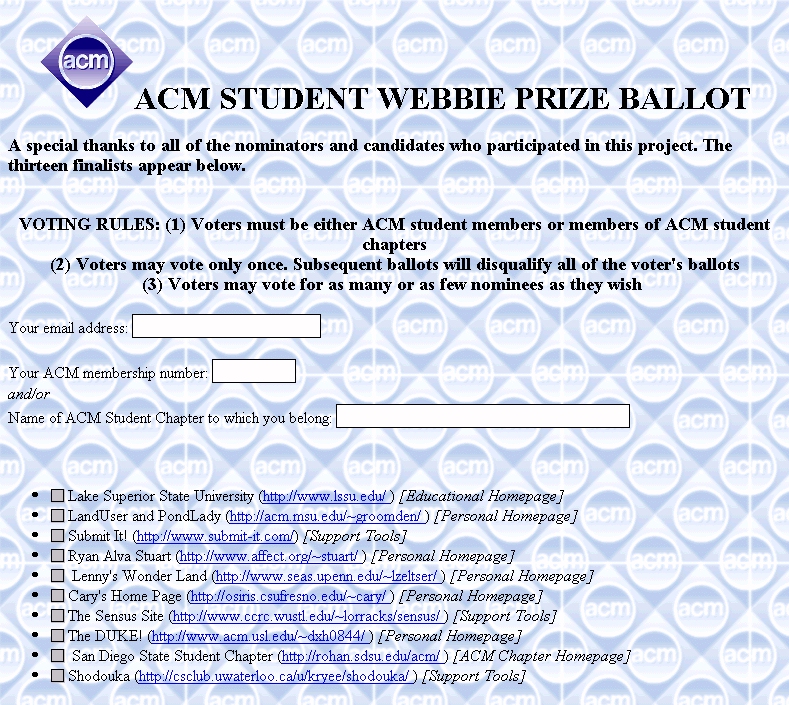

Along with some students I next created an ACM KIOSK that featured three innovations that I found inspiring. First, it had a permanent online calendar that could be personalized for all ACM members so that they could choose conferences, events, publications, elections, etc. of interest that would automatically be entered in their personalized calendar as they were announced by ACM HQ. The member could then log into ACM.ORG, look at their calendar, and choose the ACM products and services that they wanted to populate their personalized calendar. The prototype, called Dynacal, was jointly developed with one of my graduate students, Pawel Wolinski, and a colleague, Doug Blank, and worked splendidly. [ACM CALENDAR -IMAGE ATTACHED] The only problem with the prototype was that it was CGI-based (that was how web interactivity was handled in those days), so it wasn't scalable as all of the calendar data would have to reside on the ACM servers. When I demonstrated this for MAB, I pointed out that it couldn't be ready for prime time until we could figure out a way to offload the code via client-resident scripting. I still think the idea was a winner.

The second KIOSK feature was the ACM Volunteer Hotline. This was an interactive site that allowed HQ to advertise volunteer and staff positions and accept applications online – an ACM-oriented version of monster.com. When I initially posted the proof-of-concept website to try it out I used Lillian Israel's email address as the destination for the CGI form much to her discomfort when some ACM members stumbled across it and began filling her inbox with inquiries. She was not amused as I recall - another proof-of-concept to meet an untimely death. Picky, picky, picky.

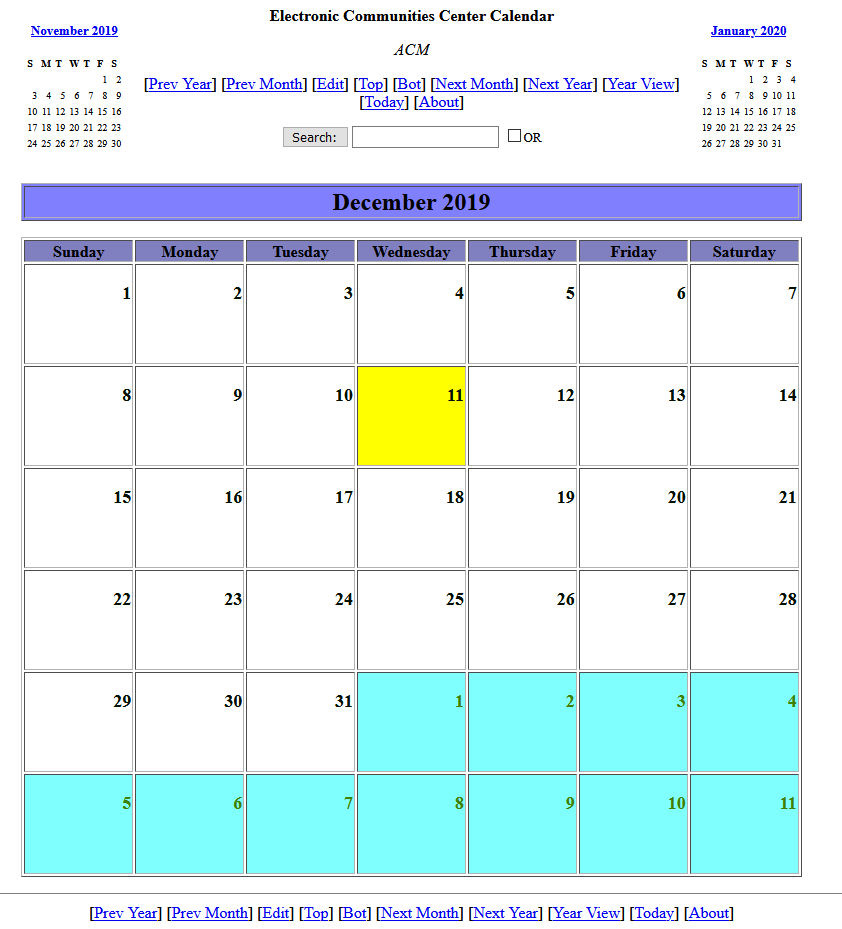

The third KIOSK feature was ACM Blackjack which I created to engage ACM prospects. [cf. ACM BLACKJACK - IMAGE ATTACHED] You could play online blackjack for “ACM Advantage Points for ACM Promotions” under your name - every 1000 points would entitle you to a complimentary copy of a magazine, journal, coffee mug, ACM T-shirt (which I developed for student chapters – I also took ACM into the clothing business!) etc. I remember when I demonstrated this for LAB, that Joe DeBlasi was concerned. He didn't think ACM should be associated with gambling. I didn't see a problem, but then I live in Las Vegas. I thought highly of the KIOSK, but I batted 0 for 3 as far as further support from ACM was concerned. Two final comments on the ACM KIOSK: First, these interactivities were done in the 1994-5 time frame and in my opinion still stand the test of time. They are/were worthy of ACM development as all of the ideas are now web standards and represent missed opportunities. But others saw it differently, so there you have it. Second, for historical reasons I wish that more of these online resources were maintained and date-stamped on ACM.ORG servers. I suggested that to the ACM leadership without effect. Unfortunately, only a few fragments remain and so this online legacy is largely lost. In addition, were they preserved and maintained ACM could legitimately claim innovation credit. I have been contacted by law firms over the years who wanted me to document our ACM Blackjack development with the goal of helping them contesting some of the online gaming patents. I have always declined such expert witness work as undignified, so I declined. However, it might have been useful had ACM chosen to stake out a few of these claims even without benefit of patent.

Following on the heels of the KIOSK, my next TOP project was a joint effort between HQ and MAB in 1996 called the ACM Community Center Project. Although most of the documentation of this effort is lost to history, a final report still remains on my website ( http://www.berghel.net/publications/acm-ecp/acm-ecp.php ). As it explains, the charge of the committee was to develop a foundation for an electronic community center for ACM. Peter Denning was engaged in a similar project for the PUBS board that ran concurrently, but his was more tightly focused on marketing ACM products and services. The CCP was more focused on the electronic communities themselves. I just re-read the report a few days ago and was caught that the report electronic communities “may allow the computing community to take advantage of whatever virtues (if any!) quasi-independent or relative identities” might afford the members. Even, 25 years ago we were suggesting to ACM that building anonymity into online services was likely to have attendant risks! Foreshadowing?

Sometime in the late 1990s, Dave Oppenheim quit MAB and David Arnold succeeded him. David asked me to stay on as vice chair to continue with TOP which I did for a few years. My last major effort on behalf of TOP/MAB was the ACM Timeline of Computing (circa 2000). This was an online interactive website that was built with one of my graduate students, Jianghong Song. There's an interesting story behind that as well. I had come to know past ACM president Tony Ralston over the years and met with him in London (where he then lived) on a visit. I had previously contributed to his popular Encyclopedia of Computer Science series. At the meeting I shared my vision that future encyclopedias should be online and interactive (cf. my CACM article in March, 2001) and I thought that the two of us should work toward that effort: I would handle the interactive online part, and he would help with what we both anticipated to be the most critical hurdle - how to incorporate and administer peer review. I sought Tony's involvement specifically because of his background with the encyclopedia - he knew and had access to many of the leading subject matter experts in computing. The criticality of peer review is obvious to any serious scholar who looks up a controversial topic on Wikipedia. There's a reason why CACM and Computer do not experience edit wars and Wikipedia does! Professional societies spend a lot of money on editorial review. Wikis do not and their audience suffers accordingly even though many are largely unaware. (I wrote about this in the September, 2014 Computer if anyone is interested).

That said, let me re-frame the discussion I had with Tony. I was proposing a prototype online encyclopedia in 2000 to be run on ACM.ORG. ACM had developed a Timeline of Computing heavy paper foldout that had been circulated to chapters worldwide for several decades. You could see them posted in virtually every university computing program in North America and Europe. So I thought, why not start with the data in the printed Timeline and allow the professional computing community to expand from there. Over time, we would have the definitive history of our profession. And 2000 was the time to do this while most of the major innovators were still alive. Another benefit would be that our minimalist approach would also keep the overhead low (excluding, of course, the cost of the peer review).

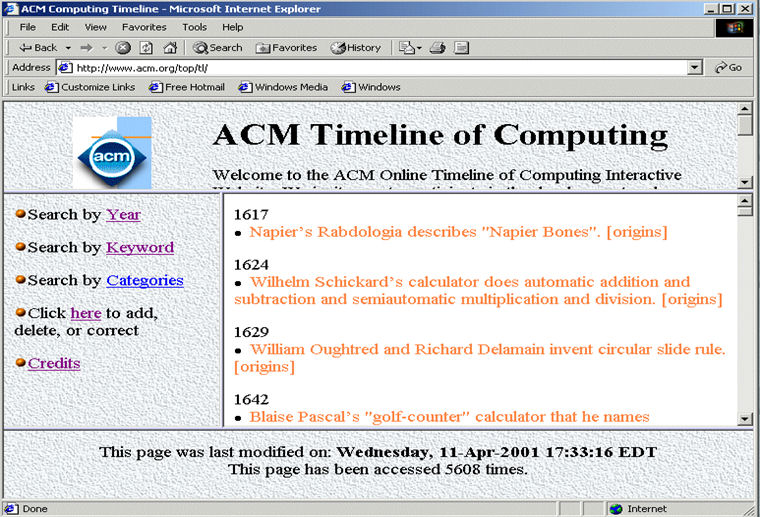

Even by 2000 the majority of the Web was gratuitous, self-serving, content-free, inconsequential, or purely commercial. By that time, gratuitous web pages like the Trojan Room Coffee Pot and real-time streaming of goldfish had given way to online hawking, idiotic rants, and self-promotion. Quality, static online resources like the ACM DL avoided this problem by front-ending the review and editorial costs before publication, but peer review was not on most Web developer's minds. That was the environment that Tony and I faced with our proposed online timeline which was announced in CACM in 2000, and fully operational by the time of the ACM-1 conference in San Jose the next year [cf. ACM TIMELINE – IMAGE ATTACHED]. As predicted, we found after the initial launch that the vetting of the contributions would take considerable resources. I reported this to MAB and HQ and told them that if we went ahead with the project it would involve a lot of volunteer resources and Tony and I didn't know how to get these volunteers without compensating them. I expand this part of the story because Wikipedia, which was launched the same year, faced the same problem. We at ACM decided that an online “x_pedia” had to be done with peer review or it wasn't worth doing. Jimmy Wales took the opposite approach and has been criticized ever since for not purging Wikipedia of built in systemic biases, light content, and misinformation. In fact, it is my understanding that the split between Wales and Wikipedia co-founder Lawrence Sanger was over this very issue – with Sanger claiming that the platform could never achieve widespread credibility until the vetting issue was resolved. What Tony and I found was that to resolve the vetting issue would require significant resources that ACM wasn't willing to bear. I thought (and still feel) that the online timeline was worth doing, even if it didn't expand into a general information resource, it would be historically interesting. But some volunteers would be needed to sustain it and Tony and I made it clear that that set of volunteers would not include us. Once again, a good idea died. There are several online encyclopedias that in my estimation are worthwhile (the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - www.plato.stanford.edu - for example), but from what I can see most consist of polemical, un-refereed tripe that serve the same parochial and tribal interests as social media sites.

By the turn of the millennium my original MAB supporters, Dave Oppenheim, Joe DeBlasi, and soon thereafter David Arnold, left ACM, and I left with them. As I mentioned, by that time the ACM focus had changed from member-centered to revenue-centered.

I'm still proud of these innovations and wish that ACM had done more with them.

CH: When did you begin writing columns in computing?

I've been writing columns in computing publications for nearly 40 years. In most cases my columns reflect my professional interests at the time of writing. My CACM column, the Digital Village (~1995-2010), reflected my growing interest in the Internet, while my column in Gaming and Leisure Magazine entitled Security Wise and my IEEE Computer column, Out-of-Band, emphasized my interests in digital security and privacy. Over the years I have written seven columns for professional publications. I am currently responsible for two columns in IEEE Computer: Out-of-Band and Aftershock.

CH: By 1996—my first year as ACM President, you received the Distinguished Service award “ For wide-ranging contributions to experimental computing and service to the computing community.” The award however does not describe what those “wide-ranging contributions to experimental computing” were—could you briefly describe them?

In a sense, the phrase experimental computing is redundant because everything that involves computing is experimental in some sense. Historically, the term has been used to distinguish the practice and research involved in development and innovation from the mathematics/theory side of our profession (e.g., algorithms, complexity theory, etc.). Most computing, then and now, would fall under the rubric of “experimental” or “applications” or “development.” That's what I did. Generally, experimental or applied research has an end-product in mind. This is to be distinguished from curiosity-driven research typically supported by federal agencies.

CH: You were named an ACM Fellow in 1998). At the time, ACM had recognized less than one-half of one percent of its membership as Fellows, prestigious indeed, especially compared to much broader Fellow recognition given by IEEE (which you also won). How do you view these two acknowledgments? I notice that you list them first on your bio page.

I very much appreciate these recognitions. The most important recognitions are those that are given arms-length by the longest arms, and these fellow awards fall into that category. I'm pleased to be so recognized.

CH: Did you see Cherie Pancake's article about Common Myths re ACM Awards? Reaction?

I did. I basically agree with her. The awards are a product of the accomplishments of the prospective awardee *and* the willingness of the nominators and endorsers to make a nomination successful. They do not purport to recognize winners of genetic lotteries, but rather reflect humble acknowledgements from peers of useful contributions to the profession. I interpret Cherie's remarks to mean that it is a mistake to view such awards as a product of some sort of optimal rank ordering. It's not like that at all. These awards are just snapshots in time that reflect one perspective of valued contributions to the profession from that part of the peerage that chose to get involved. There are many perspectives possible and many different groups of peers, and there is no reason to believe that any given awardee slate is optimal in any sense. Awards are an expression of appreciation and not the product of a contest.

CH: In my view, your most significant ACM Award is the Outstanding Contribution Award, in 2004 . That citation reads:

“For significant and wide-ranging contributions on behalf of the ACM Membership and Publication Boards, ACM Technology Outreach Programs, and the ACM Distinguished Lectureship Series.

Hal Berghel's contributions to ACM and the computing profession are as multi-faceted and energetic as his research. Hal was the driving force in creating the ACM SIG on Applied Computing and its associated journal. His major role in the ACM Technology Outreach Program (TOP) began with the revitalization of the ACM Lectureship Series which he then extended to Mexico and Central America. TOP has organized meetings around the world to assist in ACM chapter-formation activities, including India, Korea, Japan, China, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand. In all, nearly three dozen new chapters have been established as a result of this TOP initiative in the past 5 years. Hal also provided the motivation behind the first foreign language translation of an ACM periodical, Crossroads . Another form of innovation is illustrated by his development of the ACM Video Library and the Video Podium series. Further, Hal writes a regular column (Digital Village) in the Communications of the ACM and serves, in varying capacities, as a long-time member of the Publications Board. While Hal has been involved in many more activities than this sampling documents, it does convey something of the energy, zest and range of accomplishments that Hal brings to the profession.

Earlier than this award, you were a key member of the Computing Research Board. This group has been instrumental for promoting computer science research for America (and the world, actually). How did you become involved, and please describe the group and its focus for us.

HB: Actually, I was never on the CRB. I was, however, an early member of the CRB's IT Deans Workshop that brought together Computing, Information Science, and Informatics Deans to discuss future directions of the computing profession (I was associate dean for new programs at the time, and informatics was one of our new programs). This was about twenty years ago. At that time, other computing programs beyond computer science and computer engineering were serving niche student audiences. There were some disciplines that were computing intensive, but not strictly speaking computer science. These included technology centered disciplines (Computer and Information Science, data mining, text retrieval, interactive web development and multimedia, online gaming, scientific computing, etc), domain centered disciplines (Bioinformatics, Cheminformatics, Health Informatics, music informatics, modeling and simulation, etc.) and human centered disciplines (human computer interaction, social and organizational informatics, computing security, etc.). By the late 1990s some of the more progressive universities had created free-standing colleges of computing that went beyond the traditional math/computer science model. [Georgia Tech had a college of computing, Cornell had a College of computing and information science. Michigan had an information school, etc.) It became pretty clear to many of us that these universities were on to something important: the field of computing was expanding beyond the original computer science model. CRB created this workshop to bring together administrators whose institutions were interested in pursuing the concept of a free-standing college that would not be apart from science and engineering colleges and that might include such disciplines as computer science, information science, informatics and some form of advanced information technology. Some of this background may be found in Peter Denning's article The IT Schools Movement in the August, 2001 issue of CACM and our article A Paradigm Shift in Computing and IT Education that appeared in CACM in June, 2004.

CH: And especially describe the first Federated Computing Research Conference in 1993. Where was that? Is this what became known as the Snowbird Conferences?

HB: The Federated conferences were hosted by the CRA, but initially funded by ACM, the Computer Society, and other related computing organizations. I felt that the drive for these conferences was elitist due to a heavy concentration of theory, and that their activities could easily be subsumed under the ACM, CS, IEEE, etc. and was not supportive of ACM support when the topic was brought before the PUBS and MAB – but I was out voted.

Snowbird was and is an entirely different animal. It is a bi-annual meeting for computing administrators, primarily department chairs and heads. I attended Snowbird for many years when I was a chair. The CRA, through Snowbird volunteers, conducts the Taulbee Survey, incidentally.

CH: Let's shift gears slightly, to more recent topics. You've been long cited as one of ACM's most prodigious lecturers—Outstanding Lecturer four times!!! Can you quantify this for us a bit? How many courses taught, how many students reached, favorite topical points, etc. Describe the process, and in particular, if you wanted to stimulate others to emulate your model, how might you approach that?

HB: In addition to my university teaching responsibilities of several classes per year for many decades, I have also offered hundreds of lectures worldwide – either as an invited guest, a keynote speaker, as part of the ACM DLP, or as part of the IEEE DVP, etc. If anything distinguishes my lectures it is the passion that I put into the talks. In addition to the content, I pride myself on making the talks entertaining. The reason that I received the Lecturer awards was that the audience feedback was consistently positive. As I mentioned above, when I set up the DLP, I required the chapter to evaluate every speaker in terms of interest of topic, presentation quality, quality of media, overall knowledge of the topic, size of the audience, etc. The selection of the annual awardees was an accounting issue – highest scores won. I was in a friendly competition with Yale Patt over the years and I'm sure if you asked him this question, you would get a similar response. You can usually identify a good lecturer by the audience feedback. It's not rocket science – the audiences appreciate the speakers who come prepared and work hard to make the experience both interesting and enjoyable.

CH: Your website includes so many avenues to pursue, that it is hard to distinguish just one or two areas. One that particularly intrigued me was “Audience feedback to my lectures”. The first two items listed are two groups that I have personally been members of, so they naturally caught my eye:

"Hal is a very engaging speaker. He distills complex technological issues, into accessible, and thought provoking conversations."; Santa Clara Valley Section of the IEEE Computer Society, March 22, 2016.

"Your presentation to our group in Colorado Springs was amazing! Wow! Way more than I expected. Wish there wasn't so much 'interesting' information to share about that topic ["the Assault on Privacy"] but appreciate you sharing it."; Pikes Peak IEEE CS Chapter, July 23, 2014.

HB: That's related to my answer, above. This is just some of the feedback I've received in recent years. Apparently, I started putting these responses on my website in 1995. Although the feedback is flattering, it was the quantitative feedback score from the chapter audience that triggered the ACM recognitions as I mentioned.

CH: I'm not familiar with the IEEE CS Golden Core award. Can you provide some insight into that award, and becoming its recipient?

HB: I wasn't aware of it either until I received it. Apparently it is automatically given to every awardee of a major IEEE award.

CH: Your range of speaking topics in recent years is daunting—Privacy, Cybersecurity, Money Laundering and Digital Crime, the STEM Crisis Myth, Fake News, Net Neutrality, and both the 2019 College Admissions and Cambridge Analytica scandals among them. You have shown an amazing ability in my perspective to “stay current” which is rare among our elders in the field. How have you been able to sustain your own learning to stay topically up-to-date?

HB: For starters, I haven't had a television in 25 years, so I minimize that source of distraction. I resonate with Aldous Huxley's observation in Brave New World Revisited that humankind has a seemingly infinite capacity for distractions that prevent them from dealing with matters of real importance. Newton Minow was thinking along the same lines when he called TV a vast wasteland in 1962. Incidentally, I recently wrote a piece in Computer on this subject called Newton's Great Insight (Minow not Isaac) arguing that Minow didn't go far enough. TVs “vast wasteland” has evolved into the Internet's far vaster cesspool of disinformation, lies, personal attacks, trolling, etc. I received a very nice thank you from him for rekindling interest in his speech (he's close to 100 years old and still active!). Of course he didn't realize in 1961 that our forebears in computer science were already busy inventing a packet-based digital network infrastructure that would open a real toxic can of worms at the hands of digital denizens of darkness (aka authoritarians, demagogues, and politicians). As an aside, the forthcoming 2020 US presidential election will add new dimensions to the phrase vast wasteland as we witness historically unrivalled disinformation carpet bombing at the hands of partisan tribalists through the mechanism of weaponized social media.

At a very early age I developed a robust sense of situational awareness – no matter whether political, professional, or social. I still recall how my fourth grade teacher's proclamation that Columbus discovered America failed my smell test. (James Loewer documented such things in his successful book, Lies My Teacher Told Me). That prepared me for my college introduction to the widespread use of epistemological relativism and political propaganda. So I was well-prepared for the digital fake news era we currently live in. The many articles I have written about the topics you mention were half a century in gestation. My intellectual preparation was pulled into focus by the Nixon presidency and has remained there ever since. It is this over-arching ethos that I brought to CACM in 1982 in the article on the Apple bill and remains with me today.

So I'm naturally drawn to study the mis- and dis-information that surrounds current issues (applying the same smell test I had in fourth grade). And when it comes to the digital world, I speak out about it. To illustrate, I've given dozens of invited talks about digital crime – I've been conducting research with law enforcement on this topic for decades. However, it is rare to find anyone in the audience who can put digital crime in a quantitative context. For example, the total amount of illegal drug sales per year in the US is less than 20% of the total amount of lost revenue due to tax cheating. According to government reports, our war on drugs has not diminished drug use, but rather has brought down the price by 90% and increased the potency and availability. So when a politician champions the war on drugs the first question I think of is what planet has this person been on for the past 50 years? The war on drugs increased the supply of less expensive, stronger drugs, so how is that a success? So I naturally look behind a story while following the money and power. That's the way I approached net neutrality and the college admissions scandal – most of the noise surrounding both issues was mis- or dis-information, plain and simple. So I felt obligated to try to correct the record with the facts that went unreported in the telling of the story. In my recent piece on the college admissions scandal, for example, I point out that “bribing” prestige universities to admit otherwise unqualified family members goes back centuries. Lori, Felicity, et al, simply went about it the wrong way, and got taken in by charlatans. Had they lawyered up like the major players in the country club set they could have achieved their objective with little or no risk. An experienced law firm could have done their bidding without risk. But approaching the problem by bribing college coaches was a non-starter.

I'm one of many who have pointed out that the alleged crisis in STEM education is bogus! Supply and demand works the same in STEM education as it does in any other area. This is one of the principles that Adam Smith nailed in Wealth of Nations. The STEM crisis myth is a byproduct of an effort to arbitrage labor costs. ECON 101 tells us that if a “pretend crisis” can produce a labor surplus through H-1B visas and government support of STEM education, the result will be lower labor costs which will lower employer overhead and increases profits. The permanent political class has largely bought into this absurdity because there's no political penalty. They get the largess from the lobbyists, support from the IT industry, and a pass from the electorate who is inclined to view any support of education as a public good without question. This is a rerun of the Apple bill I wrote about 40 years ago which enjoyed industry support and that, in turn, fueled congressional enthusiasm. In both cases, the lobbyists understood that most citizens will refuse to look into the underlying economics of wealth redistribution and instead support any contribution toward education – even if it is counter-productive. I encourage readers to compare the Apple bill with the STEM crisis myth and identify the political similarities. One of my greatest disappointments is that our profession typically remains silent on such distortions of the body politic, when most of us should know better. We are in the best position to explain these phenomena, and yet choose to do so whether for fear of employer retaliation, diminished future job prospects, or whatever. If knowledgeable professionals don't speak out, the country wanders further and further away from constitutional principles. I encourage the reader to compare the situation of the programmers who participated in Volkswagen's dieselgate scandal with the back channel discussions between the White House and Ukranian President Zelensky. The quote “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing” is appropriate here. While scores of famous people have uttered this quotation, very few have taken it to heart.

As a final example, as I write this Attorney General Barr has just announced the indictment of four Chinese military personnel for the Equifax hack. Good luck serving those subpoenas, Bill. The claim is that these Chinese renegades have really hurt the American people, and thus deserve special prosecutorial attention. However, the Republican, pro-business Senate came to an entirely different conclusion in its 2019 report where it found that it was the feckless Equifax security policies and practices that made the hack possible. What Equifax did through their lame security infrastructure was create what lawyers call an attractive nuisance – and that drew hackers to Equifax like bees to honey. Anyone who bothers to read the Senate report will see Barr's disingenuous partisan puffery for what it is. Setting aside the problems of cyber-attribution and assuming that Barr's accusation satisfies the evidentiary standards of the U.S. courts (which I doubt), if the Chinese did commit this hack that effected half the adult population of the U.S. Equifax should at least be considered a co-defendant for their negligence. Incidentally, Equifax' has agreed to compensate the 150 million victims with $3/victim! And in order to recover damages, under Barr's DoJ, victims have to prove up damages – i.e., prove that any damages sustained can be directly attributable to this particular hack – which is in principle impossible. I encourage all computing professionals to study the Equifax hack in this political context and speak out. Equifax is living testimony that not every thing a corporation can do is net positive for society. I recently suggested in Computer that Barr should sue the Chinese government for $14 trillion on behalf of the Equifax victims. That suit won't go anywhere either, but the victims will be happier knowing that they won't get $100,000 than that they won't get $3.

While I'm on this subject, I should mention that science and the academy cannot be separated from politics. The position taken by former EiC Mosche Vardi in the March, 2013 issue of CACM is precisely wrong In this regard. If scholars (computer scientists and engineers, and academics of all stripes) do not get involved in politics they will concede major policymaking decisions to those less informed, thereby contributing to an increased level of noise surrounding policy discussions. A classic example of this is the argument that George Shultz laid out in a 1985 Foreign Affairs article called the Dictator's Dilemma. Therein Shultz presents the false dilemma that dictators have to either choose to open their information portals or watch their economies suffer. As near as I can tell, that claim went largely unchallenged by academics and journalists. One only has to look to China to see the absurdity of his position, yet Shultz's naïve position was taken by many as an article of faith (I have a reply in the July, 2016 Computer, b.t.w.). My point is that if academics and scholars remain silent on political issues, the narrative will be driven by partisan tribalists like Schultz. As another example, consider the story of the Texas junior high student who took a disemboweled digital clock to class in his military-style pencil box with the apparent intent to set the alarm off and annoy or scare a teacher or two. When the teacher and principal called in the cops the story went viral. Obama and Zuckerberg praised the kid for his ingenuity, while the talking heads of the right wing media accused him of creating the front half of an IED. As I pointed out in my article on the subject, if this kid's disemboweled clock is “half a bomb” then so is everything connected to the Internet. Where were the academics, programmers and engineers who knew (or should have known) that the kid didn't invent anything – he just took apart a digital clock? And why didn't they try to diffuse the dystory before it went viral? One of the great failings of our colleagues these days is that they all too often refuse to speak out on such things and hence concede the narrative to partisan illiterati.

CH: A recent article in Computer credits you for coining the term “disinformatics.” How did that come about?

HB: The coining of the term disinformatics was attributed to me in an article by Lori Cameron in the February 2018 issue of IEEE Computer. She suggested that I was the first person to use the term “disinformatics” to denote the scholarship associated with the study of disinformation, fake news, <alt>-facts, etc. I had argued that disinformation is so ubiquitous that courses should be offered in high school at the latest. Although I may have coined disinformatics, I'm not the first to understand its importance. Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, George Seldes, I.F. Stone, Neil Postman, etc. all understood the concept years ago. In fact, media and Internet scholar Howard Rheingold has been offering an online course in Crap Detection for many years that is basically a class in defensive disinformatics. In fact, the phenomena had been well understood at least as far back as the 1920's with the appearance of Edward Bernay's book, Propaganda. The social cohesiveness of societies has always been undermined by lies, disinformation, bullshit, etc. but social media and the Internet have exacerbated the problem, and the prime beneficiaries are what social-psychologists like Bob Altemeyer call right-wing authoritarians (the left-wing authoritarians like the Baader-Meinhof Gang, Weather Underground, etc. don't seem to be in the news much these days, in no small degree due to the fact that they're either dead or incarcerated.)

CH: Are you still doing research? Briefly describe this please.

Absolutely. Although I've shifted away from the collaborative research that I did when I administered research centers to individual research on technology policy, security, privacy, electronic crime, digital politics, and the like. Frankly, I am fearful that if computer practitioners don't take a more aggressive role on social issues in computing, society faces a digital dark age. The end result of tribal abuse of networks and social media will be a road to serfdom that's a lot scarier than Fredrich Hayek predicted.

CH: Are you still teaching?

HB: Yes. I teach courses in social issues and digital security and forensics at both the undergraduate and graduate levels at UNLV and still give occasional invited talks when convenient.

CH: What advice do you have for current CS students?

HB: By that I take it you want me to offer advice that they wouldn't normally get from any other computer science professor or advisor. Well, first and foremost, pursue your studies passionately. Approach classes as portals not contests or competitions. Unfortunately, modern education (especially in the sciences and engineering) are too de-contextualized owing to the fact that those in such disciplines try to pack more and more formal, discipline-centric content into the degree programs while not increasing the number of credit hours required for degrees. One consequence of this is that we've created undergraduate cultures that are far too narrow, intellectually, while we've decreased the number of required credits in other disciplines. The combined effect is education by tunnel vision. Computer science students would benefit far more from humanities courses than more technical electives. Disclosure: most of my colleagues do not share my opinion!

The second piece of advice I might offer is to pick a moral compass heading and stay the course. In recent years we saw Volkswagen programmers write engine management module code specifically to circumvent EPA regulations and circumvent import certification, and as Aviel Rubin has so well documented in his recent book, Brave New Ballot, programmers who wrote outrageously lame code for the Diebold Accuvote voting machines that dominated US national elections for a decade with little if any concern for security. [While I'm on this subject, I would be remiss if I failed to plug the seminal book on the frailties of modern digital election systems was co-authored by past ACM president Barbara Simons and computer scientist Doug Jones - Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count? I recommend this book to all computing professionals!). So I encourage my students to read the ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, and take it seriously. The fact that the American Psychological Association's membership recently fired its leadership for corrupting their Code of Ethics to accommodate the Bush administration's extraordinary rendition program shows that professionals do stand by codes of ethics, and the ACM has a strong one that is worthy of our consideration.

The final piece of advice would be to stand for something. A profession – computing or other – is much more than a job. It is a reflection of who we are, what we are, what we believe, and what we stand for. It cannot be de-coupled from social responsibilities and civics. So do what you do enthusiastically and with pride, and stand behind it. And take every opportunity to share your work with others.

CH: How do you view the various governmental and corporate approaches today re: social media, privacy, cybersecurity, technology policy, etc.

HB: This is a very provocative question. As far as corporations are concerned, my short answer is that the only corporate environment that I've ever had much confidence in re: security, privacy, etc. is the tech sector – and I've been losing confidence rapidly in it as well -- especially with the social media crowd. It says a lot when people my age are left with Bill Gates as an exemplar of moral rectitude. Tech-centric, socially grounded, and ethical innovators and leaders are in short supply these days, having been displaced by managers, venture capitalists, and accountants. It is not by accident that computing innovation is no longer as innovative as it was 50 years ago. To be clear, I'm claiming that the societal contributions of Facebook and Google aren't value-competitive with those of IBM, Intel, H-P and even Microsoft for that matter.

The government has been ineffective at advancing most important agendas with respect to the areas you mentioned. I would even go one step further. All too often, when the government has taken the initiative to change policy, the result has been counter-productive. I don't expect the government to fix much; but I do expect it to avoid making matters worse – and our government consistently disappoints in this regard. Legislating is particularly bad when it comes to issues of social significance – from kill switch legislation, to 9-11 swatting legislation, to the DMCA, the CAN-SPAM Act, Sarbanes-Oxley, Gramm-Leach-Bliley, HIPAA, the STEM Opportunities Act, you name it – all pretty much misguided and counter-productive when it comes to social responsibility, instead catering to corporate and partisan interests. When is the last time that you heard of a member of a corporate leadership team convicted and sentenced for a SOX, GLB or HIPAA compliance violation? The current administration is now pardoning politicians for bribery, giving false testimony to the FBI, and obstruction of justice for goodness sakes. In that sort of climate, prosecutors cannot be expected to be in a lather about HIPAA violations and tax evasion. Anything short of blatant, massive control fraud (e.g., Bernie Madoff, Jeff Skilling, Bernie Ebbers, etc.), these days is unlikely to be prosecuted at all and even then its iffy if it involves less than many millions of dollars. To any doubting Thomases out there I recommend William Black's book, The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One. The difference in the way federal prosecution worked in the 1980's Savings and Loan Scandal and the 2007-8 banking failures is very telling about the moral climate of government and its commitment to the citizenry.

There is so much ill-conceived legislation affecting the computing community that I can't write fast enough to keep up with the critiques in my columns. Unfortunately, there are too few of us making our opinions known. Hopefully, some of the computing professionals who read this will accept the challenge.

Let me conclude with a few egregious examples of government and regulatory failures. First, Ajit Pai's overturning of Obama's net neutrality FCC policy is a mistake of the first order and it is inconsistent with the “dumb pipe” philosophy that has driven the Internet since its inception. I think that computer professionals should openly and aggressively challenge Pai's claim that corporate profits drive Internet innovation, and speak out accordingly, because Pai and his telco/ISP cronies (Pai's qualifications for the FCC was as an attorney for Verizon) are destroying the fabric of the digital playground that has allowed all of us to prosper. One only has to look to the T-Mobile “Binge On” protocol experience to confirm the extent of the absurdity of allowing ISPs and telcos to toy with the dumb pipe philosophy. I would encourage every computer professional to remember that the Internet was designed and implemented by scientists and engineers and not by politicians, corporate executives and lawyers.

Second, lack of a functional Federal Election Commission for the past several years will ensure that no standards recommendations will be put forth to ensure faithful implementation of either the one-person one-vote principle or full compliance with the spirit of the federal voting rights legislation – two principles that I (and earlier Supreme Courts) believe are fundamental to our republic. As a result, we will be left with institutionalized and politicized vote suppression for the foreseeable future. While no empirical evidence has yet surfaced that supports claims of voter impersonation fraud (that's the reason there have been virtually no convictions), there is ample evidence of continued vote suppression (e.g., caging, purging, voter disenfranchisement, vote nullification, vote dilution through redistricting and at-large elections). Without a quorum, the FEC is guaranteed to do nothing with respect to vote suppression. I fully understand that this is by design, but I don't understand the public indifference.

And while we're on politics, very few computer professionals recognize the importance of the scientific study of gerrymandering – which has been particularly noteworthy since redistricting based on the 2010 federal census. In fact, far too many people believe that gerrymandering is concerned with re-electing incumbents. That's at best a secondary goal. The primary objective of gerrymandering is to find an optimal redistricting cover so that one party may maximize the congressional or legislative seats gained with the minimum number of supportive votes. Computer scientists have created the algorithms (e.g., Maptitude by Caliper Corp.) to find such covers. This tactic was implemented effortlessly by project REDMAP in 2012 where the party with the least national total votes gained a majority of seats in Congress and state legislatures. What most fail to recognize is that the goal of partisan gerrymandering is the maximization of the efficiency gap – a measure of the efficiency with which votes are translated into election outcomes. When political partisans “pack,” “stack,” or “crack” elections, they're really just forcing opponents to waste votes (you only need one vote to win an election in our winner-take-all system, any more than that is wasted). Since nothing is more important to a democratic government than having fair elections, wouldn't one think that computer scientists would study these algorithms as undergraduates? What is more, university faculties are largely ignorant of the work that has been done by computer science researchers, even though there are dozens of faculty involved. The next time you give a talk on the future of computer programming, ask the audience to name one computer scientist who has published in this area and count the responses. Isn't an important goal of education to produce responsible citizens? Of course the literal constructionists argue that universal suffrage was never seriously considered by the founding fathers (which is true). But then neither was the abolition of slavery.

March 9, 2020

Las Vegas, NV